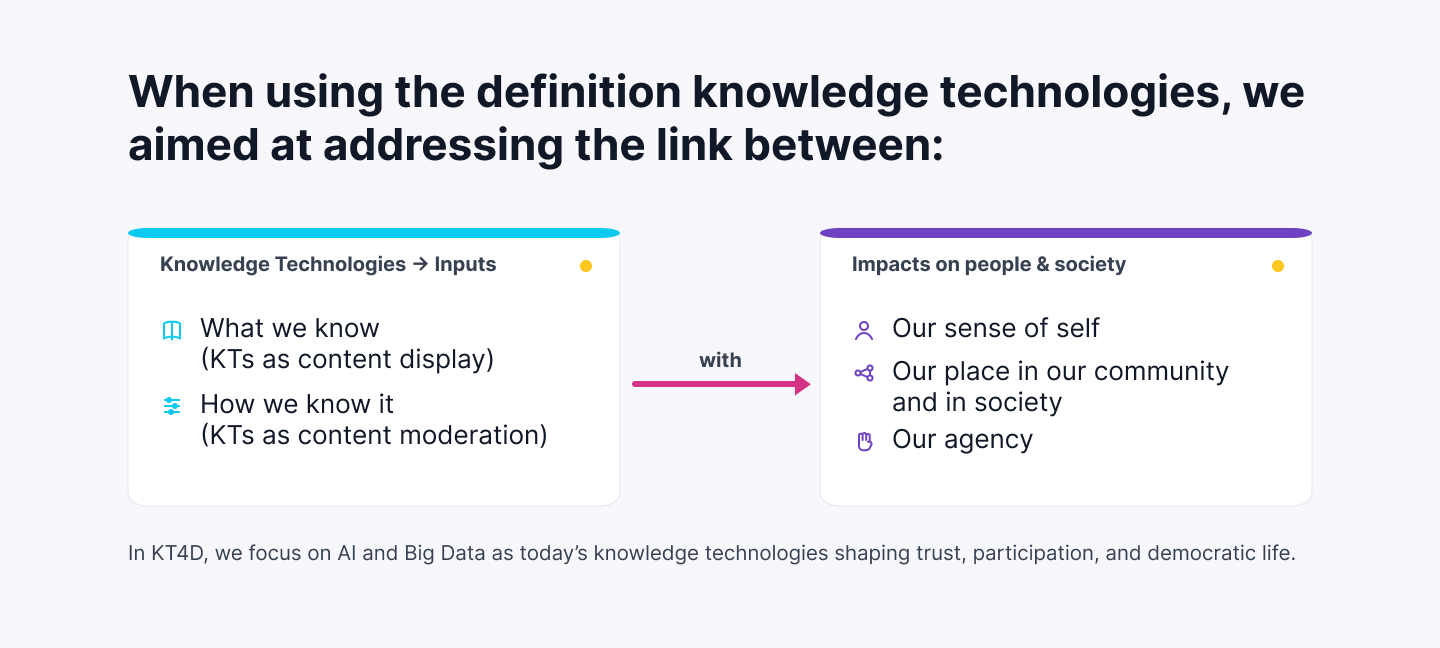

Knowledge technologies are not just tools for storing or delivering information. They are systems that shape how knowledge is formed, filtered, and made meaningful. By linking what we know (the content we encounter) with how we know it (the ways it is selected, framed, and moderated), these technologies influence our sense of self, our place in society, and our ability to act. From the printing press to radio and television, from social media to self-learning AI, knowledge technologies do more than provide facts: they structure how people understand reality, public opinion, and one another. Because they gate access to information and shape how meaning is produced, they create both opportunities and risks for democracy – making them central to how power, participation, and belonging are organised.

In KT4D, our focus is on AI and Big Data as the latest manifestations of these knowledge technologies.

Limitations of the existing definitions of knowledge technologies

The term ‘knowledge technologies' has not been used extensively (24,800 results on Google Scholar compared to 1,670,000 results for ‘information technologies’) and definitely not in a critical way, but more as an operational definition. The term was a more popular definition between 2000s-early 2010s and it was often used to indicate practical tools (often software) for knowledge management (Garavelli et al.), or to talk about the Semantic Web (Rigau et al.). This means that knowledge technologies are usually intended solely as digital and computer technology (Milton: 13). The definition is also found in publications and projects written by scholars who are not native speakers of English (many in the Balkans and Eastern European countries, and Italy) and whose main audiences are not Anglophone academics, used probably because it provides a more literal and thus accurate translation. More recently, the label ‘knowledge technologies’ has been used to designate educational tools – most exclusively digital ones – making remote learning possible during the COVID-19 pandemic. In these cases (Stewart and Khan; Dionisio-Flores et al.) the word ‘knowledge’ of the definition stands for ‘knowledge acquisition’ and has a specific pedagogic connotation.

This literature often considers how knowledge – understood as content – could be successfully transferred and managed by means of employing dedicated ‘knowledge technologies.’ More importantly, many of these analyses, especially the one developed within the field of knowledge management, tend to adopt the definition as self-explanatory. This is because they mostly focus on establishing what ‘knowledge’ is and, once satisfied with a definition, they assume that every tool used to share and manage it, is by necessity a ‘knowledge technology’.

Cultural and historical perspective on knowledge technologies

One of the modules in the KT4D toolkit focuses on understanding AI and Big Data in terms of the long history of interactions between technological affordances (writing, printing, television, etc.) and cultural norms, values, and practices, and notably on the particular function of AI and Big Data as advanced knowledge technologies (AKTs).

- Why knowledge over information? Because knowledge captures the “social, human process of shared understanding and sense-making” (Holtshouse 1998)

- Why the historical perspective? To uncover the evolution, trends, and paradigm shifts in KTs, enhancing our understanding of the contemporary landscape.

- Why the cultural perspective? To highlighted the socio-cultural influences shaping technological development (AI & Big Data included)

Research Questions

These are some of the research questions the KT4D consortium has addressed throughout the project:

- Is the difference between past KTs and AI and big data a matter of substance or just scale?

- How did past examples of KTs shape and enhance democratic participation and human agency? What can be learned from these precedents?

- Are they still applicable after considering changes in our personal and societal values? To what extent?

- Did past examples of KTs lead to oppressive and antidemocratic systems and reduced human agency?

- What can be learned from these precedents? How did people respond and with what results?

- Historically, which groups of people or institutions petitioned for a democratic use of KTs? Who were the groups historically left out from this progress/benefits?